Week 5 In Class Lab

(Logistic Regressions) Overview

In this practical exercise, you'll first run through a logistic regression exercise on a small, well-known dataset so that you can see how to use the code to develop a logistic regression model. Let's get started.

Step 1: Set up R environment for Lecture Example Analysis

First, as usual, set the working directory.

setwd()

Remember, if you can't get the setwd (set working directory) function to work, try ?setwd to get some additional help.

Since we'll be conducting two different analyses for this practical exercise (including the take home lab), you'll need to create a new script file for the class examples. For this week, we will work on classifications, so let's make a new R file called "LectureExampleData2" for In-Class lab and "LabExampleData2" for the Take-Home Lab.

This week, we will use the R packages ggplot2, gridExtra, and caret. You need to install them by using the install.packages() function.

To begin, we will clear our current workspace (get rid of any saved variables) and load a few packages that we'll use for the example analysis. Cut and paste the following commands into your new script file and run them:

rm(list=ls()) ##clears the environment

## Library for An Introduction to Statistical Learning with Applications in R

library(ISLR)

## Libraries for Plotting our Results

library(ggplot2)

library(gridExtra)

## Library for confusion matrix

library(caret)## Loading required package: latticeNote that if you look in the "Environment" window in your upper right hand column, all of the objects you created with your previous code have been erased from memory. You are restarting with a blank slate.

Step 2: Load, Visualize, and Split (Training vs. Test) Data Sets

Now, let's bring in the dataset that we'll be working with for the example. this is a simulated datasheet titled "Default" containing information on ten-thousand credit customers provided in ISLR. We will use the "Default" dataset to illustrate the concept of classification by fitting several different machine learning models to the data over the course of several practical application exercises. For these examples, we will develop models to "predict whether an individual will default on his or her credit card payment, on the basis of annual income and monthly credit card balance." (James et al, 2013, p. 128).

"Default" dataset is in the "ISLR" library.

##Load Default (Credit Card Default Data)

data(Default)

#Display the first few rows of data

head(Default)## default student balance income

## 1 No No 729.5265 44361.625

## 2 No Yes 817.1804 12106.135

## 3 No No 1073.5492 31767.139

## 4 No No 529.2506 35704.494

## 5 No No 785.6559 38463.496

## 6 No Yes 919.5885 7491.559## Provide a summary of the data

summary(Default)## default student balance income

## No :9667 No :7056 Min. : 0.0 Min. : 772

## Yes: 333 Yes:2944 1st Qu.: 481.7 1st Qu.:21340

## Median : 823.6 Median :34553

## Mean : 835.4 Mean :33517

## 3rd Qu.:1166.3 3rd Qu.:43808

## Max. :2654.3 Max. :73554Looking at the data, you will see that the response variable stored in the column "default" which indicates whether or not a person defaulted on their payment. There is a categorical variable titled "student" indicating student status and two numeric variables, "balance" and "income."

Let's plot the data based on the two numeric attributes to get a sense of what the data looks like using the ggplot2 package. take careful note of how we use various aesthetics to change the formatting of the plot (color, shape, etc.):

## Plot the actual data

plotData <- ggplot(data = Default,

mapping = aes(x = balance, y = income, color = default, shape = student)) +

layer(geom = "point", stat = "identity", position = "identity") +

scale_color_manual(values = c("No" = "blue", "Yes" = "red")) +

theme_bw() +

theme(legend.key = element_blank()) +

labs(title = "Original data")

plotData

We have seen ggplot2 before so this should be at least a little familiar. If you want to know more on ggplot2, type "?ggplot2."

We can see in the plot above that there is no "clean break" or simple rule that divides those that default from those that don't. We will try several different modeling approaches to find a best policy over the next few practical application exercises.

Before we begin fitting models, we need to break the data into a train and a test Dataset. We will split the Default dataset into a training dataset that includes 9-% of the observations and a test dataset that includes 20% of our observations. We do this by generating a sample of index values and then pulling data out of the Default dataframe based on the sample.

# Partition of data set into 80% Train and 20% Test datasets

set.seed(123) # ensures we all get the sample sample of data for train/test

sampler <- sample(nrow(Default),trunc(nrow(Default)*.80)) # samples index

LectureTrain <- Default[sampler,]

LectureTest <- Default[-sampler,]Setp 3: Fit a Logistic Regression Model

The code blocks below fit two different logistic regression models. The first one uses R's shorthand notation of a period for fitting a model using all features (response variable ~.). The second model uses only the two numeric predictors, and uses the scale() command to center the scale on the numeric data. The summary command provides a summary of the model fit (as discussed in the lecture).

Notice that we are using the glm function and not the lm function, but to use this, we need to tell the function what type of model we want to fit. If you set "family" to "gaussian," you would get normal linear regression.

To use the glm() function for logistic regress, you have to set the parameter "family = binomial(link="logit")."

Logit1 <- glm(formula = default ~ .,

family = binomial(link = "logit"),

data = LectureTrain)

summary(Logit1)##

## Call:

## glm(formula = default ~ ., family = binomial(link = "logit"),

## data = LectureTrain)

##

## Deviance Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -2.1526 -0.1404 -0.0558 -0.0199 3.7422

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -1.097e+01 5.487e-01 -19.995 <2e-16 ***

## studentYes -6.344e-01 2.621e-01 -2.421 0.0155 *

## balance 5.772e-03 2.605e-04 22.162 <2e-16 ***

## income 4.449e-06 9.095e-06 0.489 0.6248

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 2340.6 on 7999 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 1252.3 on 7996 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 1260.3

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 8## Fit logistic regression using only scaled numerical predictors

Logit2 <- glm(formula = default ~ scale(balance) + scale(income),

family = binomial(link = "logit"),

data = LectureTrain)

summary(Logit2)##

## Call:

## glm(formula = default ~ scale(balance) + scale(income), family = binomial(link = "logit"),

## data = LectureTrain)

##

## Deviance Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -2.2179 -0.1417 -0.0573 -0.0207 3.7308

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -6.13876 0.20999 -29.23 < 2e-16 ***

## scale(balance) 2.74467 0.12318 22.28 < 2e-16 ***

## scale(income) 0.28919 0.07453 3.88 0.000104 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 2340.6 on 7999 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 1258.1 on 7997 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 1264.1

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 8We can see that the first model using all of the predictors provides a better fit (as we would expect). However, better fit on the training data often does not necessarily lead to a better model fit on out of sample test data. Selecting the subset of features that provides the best model is a large (unsolved) problem in data science, but there are some algorithmic procedures for doing so that provide some benefit. We'll use one automated procedure called stepwise modeling below.

Step 4: Stepwise Model Selection (Feature Subsetting)

Please see the section starting at page 205 in ISLR (James et al, 2013) for an in-depth discussion of model selection. For this practical exercise, we'll apply the automated Stepwise model selection approach to the model that has all of our predictors using the code below.

# Conduct stepwise model selection

LogitStep<-step(Logit1, direction = "both")## Start: AIC=1260.3

## default ~ student + balance + income

##

## Df Deviance AIC

## - income 1 1252.5 1258.5

## <none> 1252.3 1260.3

## - student 1 1258.1 1264.1

## - balance 1 2328.8 2334.8

##

## Step: AIC=1258.53

## default ~ student + balance

##

## Df Deviance AIC

## <none> 1252.5 1258.5

## + income 1 1252.3 1260.3

## - student 1 1273.2 1277.2

## - balance 1 2330.3 2334.3# Summarize the selected model

summary(LogitStep)##

## Call:

## glm(formula = default ~ student + balance, family = binomial(link = "logit"),

## data = LectureTrain)

##

## Deviance Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -2.1723 -0.1406 -0.0559 -0.0199 3.7500

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -1.080e+01 4.141e-01 -26.077 < 2e-16 ***

## studentYes -7.333e-01 1.658e-01 -4.424 9.69e-06 ***

## balance 5.775e-03 2.604e-04 22.178 < 2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 2340.6 on 7999 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 1252.5 on 7997 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 1258.5

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 8Once the code runs, you can see that the model selected using The stepwise procedure uses only two of the predictors variables: student (a categorical Yes/No variable) and balance (a numeric variable). Now, let's take a quick look at model performance.

Step 5: Visualization and Performance of Model

Now that we've picked a model, let's add the predictions made to our dataset. We evaluate performance on the "held out" test dataset (i.e. data that wasn't used to fit the model). The code block below creates a version of the Test dataset for plotting purposes and adds the resulting predictions to the dataframe. The column "predProbLogit" adds the probability calculated by the final logit model for each observation in the test dataset. The column "predClassLogit" adds the resulting prediction on the test dataset when the value 0.5 is used as the classification threshold. We again use the summary() command to get a quick look at the resulting data.

# Put the predicted probability and class (at 0.5 threshold) at the end of the dataframe

predProbLogit <- predict(LogitStep, type = "response", newdata = LectureTest)

predClassLogit <- factor(predict(LogitStep, type = "response", newdata=LectureTest) > 0.5, levels = c(FALSE,TRUE), labels = c("No","Yes"))

# Create a plotting version of the Default dataset where we will store model predictions

LectureTestPlotting <- LectureTest

# Put the predicted probability and class (at 0.5 threshold) at the end of the plotting dataframe

LectureTestPlotting$predProbLogit <- predProbLogit

LectureTestPlotting$predClassLogit <- predClassLogit

summary(LectureTestPlotting) # look at a summary of the updated data frame## default student balance income predProbLogit

## No :1934 No :1393 Min. : 0.0 Min. : 5297 Min. :0.0000098

## Yes: 66 Yes: 607 1st Qu.: 481.0 1st Qu.:21146 1st Qu.:0.0002656

## Median : 814.3 Median :34510 Median :0.0017564

## Mean : 831.9 Mean :33527 Mean :0.0334465

## 3rd Qu.:1166.7 3rd Qu.:43919 3rd Qu.:0.0130466

## Max. :2461.5 Max. :70022 Max. :0.9530186

## predClassLogit

## No :1974

## Yes: 26

##

##

##

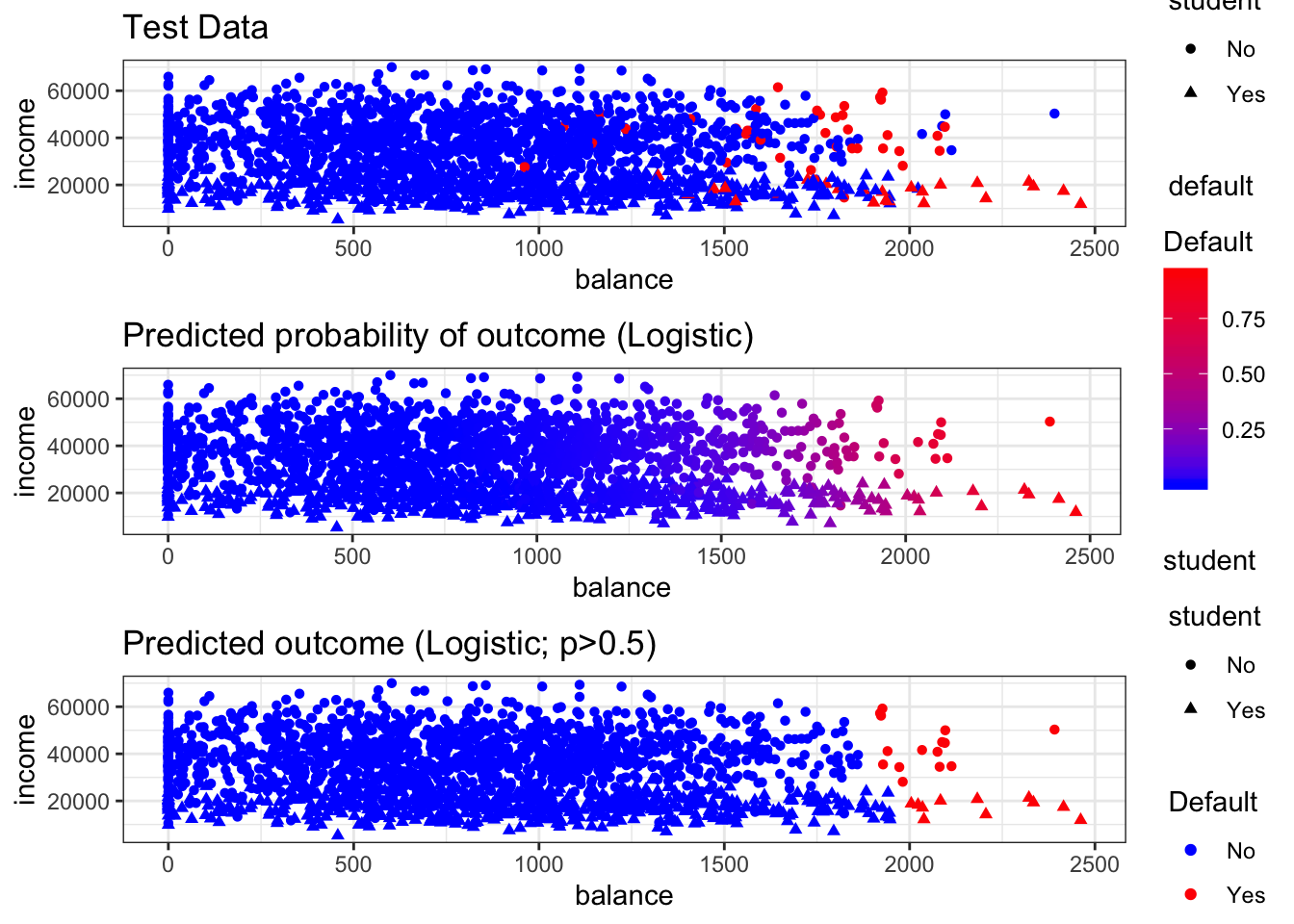

## Now we can make a visualization to take a look at how the model fit the test data. The top row below shows the actual results in the test dataset. The second row shows the probabilistic prediction made by the model. The third row shows the classification made by the model on the test dataset when 0.5 is used as the classification threshold.

# Plot the actual test data

plotTest<-ggplot(data = LectureTestPlotting,

mapping = aes(x = balance, y = income, color = default, shape = student)) +

layer(geom = "point", stat = "identity", position = "identity") +

scale_color_manual(values = c("No" = "blue", "Yes" = "red")) +

theme_bw() +

theme(legend.key = element_blank()) +

labs(title = "Test Data")

plotLogit <- ggplot(data = LectureTestPlotting,

mapping = aes(x = balance, y = income, color = predProbLogit, shape = student)) +

layer(geom = "point",stat = "identity", position = "identity") +

scale_color_gradient(name="Default", low = "blue", high = "red") +

theme_bw() +

theme(legend.key = element_blank()) +

labs(title = "Predicted probability of outcome (Logistic)")

## Plot the class using threshold of 0.5

plotLogitClass <- ggplot(data = LectureTestPlotting,

mapping = aes(x = balance, y = income, color = predClassLogit, shape = student)) +

layer(geom = "point", stat = "identity", position = "identity") +

scale_color_manual(name="Default", values = c("No" = "blue", "Yes" = "red")) +

theme_bw() +

theme(legend.key = element_blank()) +

labs(title = "Predicted outcome (Logistic; p>0.5)")

# Plot original data (top row) and predicted probability (bottom row)

grid.arrange(plotTest, plotLogit, plotLogitClass, nrow = 3)

Finally, let's calculate some performance statistics on the test data. We can get the full suite of performance statistics based on the confusion matrix using the confusionMatrix() command provided by the caret packages.

# Generate a confusion matrix and performance statistics on test dataset

confusionMatrix(data=predClassLogit, reference=LectureTest$default) ## Confusion Matrix and Statistics

##

## Reference

## Prediction No Yes

## No 1928 46

## Yes 6 20

##

## Accuracy : 0.974

## 95% CI : (0.966, 0.9805)

## No Information Rate : 0.967

## P-Value [Acc > NIR] : 0.04176

##

## Kappa : 0.424

##

## Mcnemar's Test P-Value : 6.362e-08

##

## Sensitivity : 0.9969

## Specificity : 0.3030

## Pos Pred Value : 0.9767

## Neg Pred Value : 0.7692

## Prevalence : 0.9670

## Detection Rate : 0.9640

## Detection Prevalence : 0.9870

## Balanced Accuracy : 0.6500

##

## 'Positive' Class : No

## Evaluating the performance of the model on the training dataset above, we can see that the model does a pretty good job of predicting overall, but that it isn't very good at identifying when someone is going to default at the classification threshold of 0.5. The model correctly predicts only 20 out of 66 of the people who will default at that threshold. As we will discuss further in the course, we may want to adjust our threshold depending on our problem and we may want to try to find a better-performing model (more to follow). However, the exercise above provides a code example for fitting a logistic regression model that can be adapted for our practical application problem.

Before moving on, perform the following actions to save your work and prepare for the practical application:

- Save your workspace as "LectureExampleData2.RData" (By typing save.image(“LectureExampleData1.RData”) function)

- Save your script to a file named "LectureExampleData2.R"